Benvindos à retrospectiva que preparamos

sobre o diretor Emanuel Mendes, cujo novo trabalho em curta-metragem, É Quase Verdade, está pronto para a

estreia. O filme, um documentário falso rodado em preto e branco, e o terceiro

na filmografia do cineasta, contém todos os elementos e idiossincrasias deste

gênero cinematográfico, mas também traz a marca muito pessoal de seu autor, um

cinema que não esconde a vocação para o fantástico e o extraordinário inseridos

no cotidiano de pessoas comuns. O texto abaixo traz alguns depoimentos além de

uma análise detalhada sobre os três filmes rodados por Mendes até agora – Assis & Aletéia (2002); Amarar (2008) e, é claro, É Quase Verdade (2014).

Se o cinema é imagem e som, sem a

necessidade do diálogo, como pregava o cineasta inglês Alfred Hitchcock (1899 –

1980), ou a mentira 24 quadros por

segundo, de acordo com a célebre declaração de Jean Luc Godard, ou ainda,

segundo a frase do alemão F. W. Murnau (1888 – 1930), que dizia que o filme ideal não precisa de frases ou

diálogos; por sua própria natureza, o cinema deve saber contar uma história

completa apenas com imagens, então o cinema em curta-metragem praticado por

Emanuel Mendes, um mineiro que se estabeleceu em São Paulo em 1999, segue essas

afirmações à risca. Pelo menos, é claro, os dois primeiros, Assis & Aletéia (2002), um conto de

amor surrealista inspirado por duas paixões do cineasta, o diretor espanhol

Luis Buñuel (1900 – 1983) e o pintor catalão Salvador Dalí (1904 – 1989), e Amarar (2008), também uma história de

amor com elementos do fantástico e do extraordinário, sobre uma jovem (Djin

Sganzerla, filha do enfant terrible

do cinema brasileiro, Rogério Sganzerla), perdida em devaneios, incapaz de

distinguir presente, passado e imaginação. Nenhum dos dois filmes contém falas,

explicações ou cartelas expositivas que ajudam o espectador a mergulhar no

labirinto de suas histórias.

“O que está em jogo não é a ação baseada

no diálogo, mas sim os sentimentos e sensações das personagens”, diz Mariana

Tavares, do canal Rede Minas, que entrevistou o diretor para o Festival

Internacional de Curtas de Belo Horizonte em 2008. “Os filmes não são preto no

branco, é preciso que se monte as próprias narrativas na sua cabeça. Onde

começa a realidade e onde termina a ficção fica a cargo de cada um. Dessa

forma, os filmes respeitam a inteligência do espectador”, continua Mariana. Obviamente

isso não significa uma receita pronta para o sucesso ou ao menos uma acolhida

mais confortável por parte de quem os assiste. “As pessoas se esqueceram de

pensar – estão muito condicionadas por aquilo que veem na TV, na publicidade, as

fórmulas prontas, elas querem sair de um filme tendo entendido tudo, sabendo

exatamente quem é o mocinho e quem é o vilão. Se precisam pensar um pouco mais,

se esforçar para compreender algo, ou mesmo lidar com a ambiguidade (que é uma

das coisas que elas têm mais dificuldade), e não conseguem, sentem-se burras, e

a reação imediata é rejeitar aquilo que assistiram”.

|

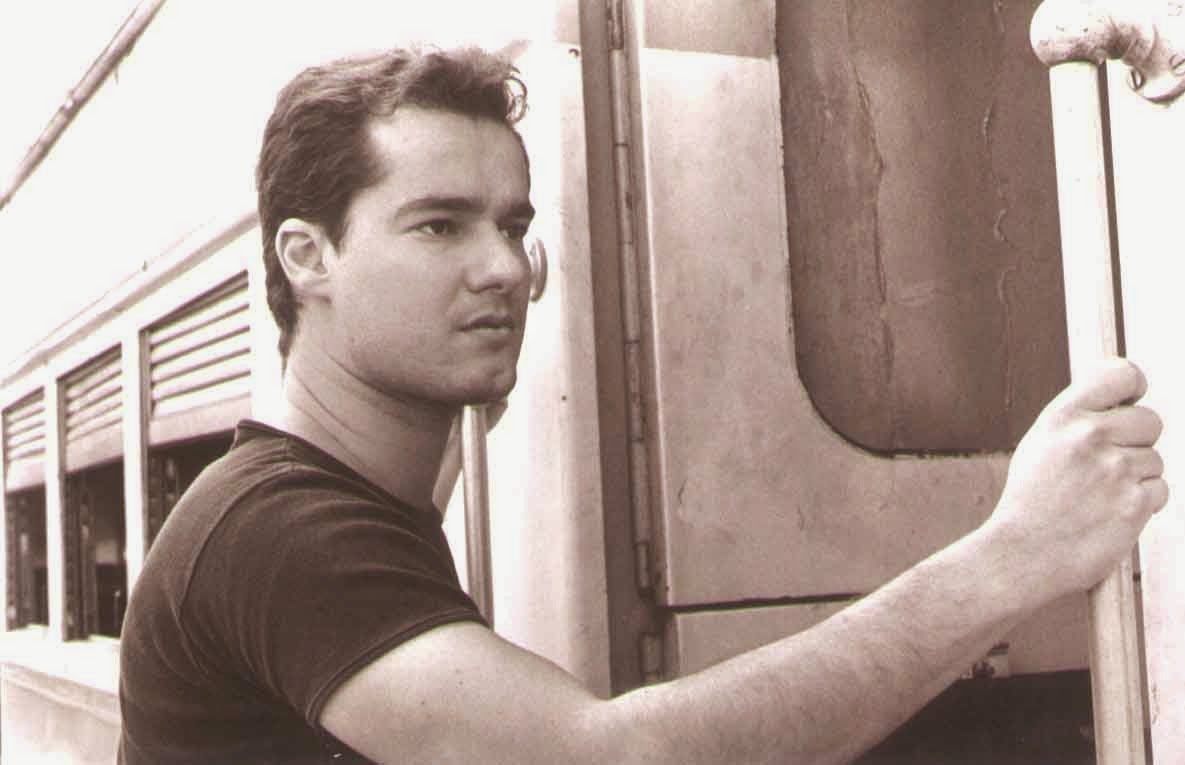

| Cena de "Assis & Aletéia" |

Assis

& Aletéia,

o curta de estreia de Mendes, obviamente não fugiu à regra. Rodado em 16mm, em

locações em São Paulo e na cidade mineira de Pouso Alegre (que emprestou a

pequena estação de trem e a locomotiva como cenários), sobre um rapaz que

encontra casualmente uma jovem (cujo rosto nunca vemos) em um vagão de trem, e

fica obcecado pelo umbigo dela à mostra, provocou os mais diversos tipos de

efeitos em festivais – desde sua primeira exibição no Festival de Gramado em

2002 até vaias, aplausos tímidos ou reações desconcertadas após o término com

diversas outras plateias. “Mas é um filme onde o estranho e o belo estão

intimamente conectados pelo desejo”, afirma Francisco Costabile, cineasta e

amigo de Mendes. “As cenas das mãos dadas com os galhos das árvores ao fundo,

ou mesmo a do lençol esvoaçante vista de longe são exemplos disso. A sensação

de estranhamento que o filme causa é muito grande, supera a ação dos atores, é

uma situação realista de se estar dentro de um trem em um contexto que não

queremos acreditar que é verdade, mas sim um sonho”.

Escrito em 1995, por Mendes e seu primo,

o psicólogo Christiano Lima, Assis &

Aletéia é inspirado pelo curta Um

Cão Andaluz (1928), realizado pela dupla Luis Buñuel e Salvador Dalí, e

considerado o marco inicial do surrealismo no cinema. A história segue o ponto

de partida do filme de Buñuel e Dalí – “ao invés de um olho dilacerado por uma

navalha, tivemos um umbigo cortado por um punhal”, conta Christiano. E há ainda

uma estranha coincidência em relação a formas circulares, ao umbigo, às rodas

do trem, ao próprio andamento da história, que começa e termina no mesmo lugar.

Uma obsessão, aliás, do cinema de Buñuel, cuja constância era quase sempre em

cima de cenas, situações e temas que se repetiam à exaustão. “Nós estávamos tão

apaixonados por Buñuel e Dalí, pelo método de trabalho deles, que chegamos

mesmo a copiá-los”, continua Christiano. “Combinamos que, se víssemos alguma

coisa inusitada ou diferente na rua, em qualquer lugar, contaríamos

imediatamente um para o outro, e partiríamos nossa história daquele ponto. E eu

vi: sentado no ônibus, indo para a Faculdade, eu não conseguia parar de olhar

para um cara à minha frente obsessivamente encarando o umbigo à mostra de uma

moça em pé.”

|

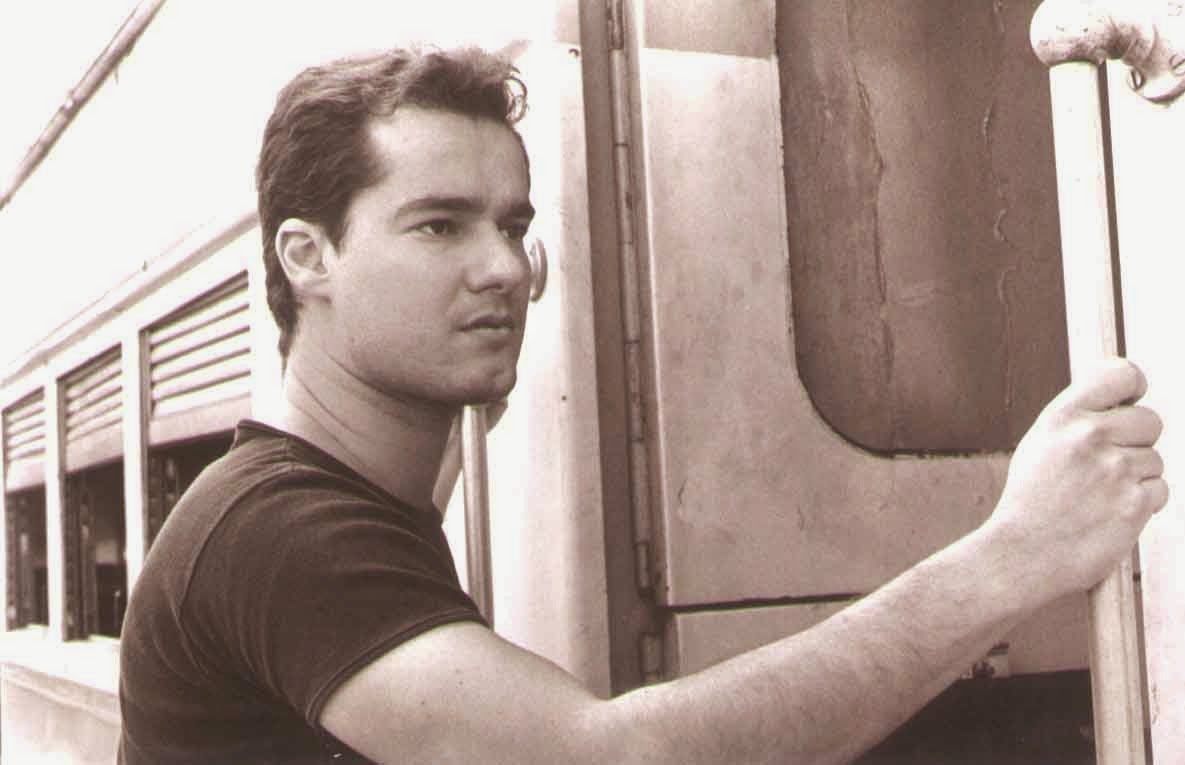

| O ator Fernando Seth como Assis. |

O resultado foi um curta-metragem

curtíssimo, de apenas 5 minutos de duração, que, hoje, Mendes considera mais

como um aprendizado, um filme cuja

intenção foi melhor do que a realização, mas que, segundo ele, serviu como

uma verdadeira escola de cinema. Todo produzido com dinheiro próprio, tendo

apenas a FAAP (Faculdade Armando Álvares Penteado), de São Paulo, como

apoiadora, com a câmera emprestada de amigos, o negativo vencido há mais de

seis meses, e uma série de outras dificuldades, mas que foram superadas pela

obstinação de um jovem diretor que, até hoje, parece não ter desertado do

constante exercício da provocação e da independência.

“Mas isso tem um custo”, diz Christiano

Lima. “O filme foi rejeitado pelas plateias de festivais, diversas pessoas

vieram nos perguntar o que diabos queríamos dizer com aquilo, e houve pessoas

que chegaram a afirmar que não se tratava de um filme brasileiro – era europeu

demais, hermético, muito influenciado por um cinema de fora”. E isso, segundo o

próprio diretor Mendes, em um formato onde a experimentação chega quase a ditar

as regras, onde se é permitido ousar muito mais do que em um longa-metragem,

que possui regras e imposições comerciais claras à sua distribuição e venda.

“Houve até quem implicasse, em alguns festivais, que o filme não possuía

roteiro simplesmente porque não possuía diálogos. Chega a ser assustador o

nível médio de intelecto por parte de algumas pessoas desse meio”.

|

| Djin Sganzerla em cena de "Amarar" |

Mas o diretor continuou fiel a si mesmo,

aos seus princípios e à sua estética com seu trabalho seguinte, Amarar (2008), considerado, por ele

próprio, o melhor filme que fez até agora – um trabalho muito mais maduro, sob

todos os pontos de vista, aquele no qual Mendes viu-se transformado em um

diretor de cinema de verdade, segundo suas próprias palavras. A começar pela

duração: 23 minutos, quando o “normal” para este tipo de formato são 15

minutos, e que ainda por cima exige uma dose maior de atenção e percepção por

parte do espectador. E onde, segundo o diretor, ele aprendeu a não cometer os

erros do filme anterior, mas sim abrir-se à possibilidade de se cometer outros.

A ideia surgiu a Mendes depois de contar ao amigo e corroteirista André Campos

Mesquita sobre uma imagem que não lhe saía da cabeça: a de uma jovem mulher,

perdida em uma praia deserta, com um enorme espelho rachado ao seu lado.

“Na verdade, essa imagem possui uma

origem muito mais remota”, conta André. “Certa vez, ele me contou, o Emanuel

foi ao Masp (Museu de Arte de São Paulo) e ficou muito impressionado por um

quadro (do naturalista Johannees Thermin)

que exibia uma mulher triste, com um vaso rachado ao seu lado. Estava ali o

cerne do nosso filme”, continua André. Depois de escreverem várias versões –

“uma a cada mês, durante seis meses, em um processo de workshop dos mais divertidos, engraçados e enriquecedores, também

cheio de dificuldades para se resolver a trama, ao ponto de nos referirmos ao

roteiro como “aquele assunto desagradável””, conta André –, a dupla realizou um

filme complexo, com muitas entradas e várias camadas de interpretação. Uma história

de amor – envolvendo a personagem de Djin Sganzerla, Noemi –, mas também um

conto sobre as lembranças de uma mulher madura (Helena Ignez, mãe na vida real

de Djin, ex-mulher de Rogério Sganzerla), ou simplesmente a narrativa de uma

garotinha com um poder de imaginação extraordinário, ou até mesmo com um trauma

de infância dos mais assustadores (a menina foi feita pela estreante-mirim

Bruna da Mata).

|

| Bruna da Mata em "Amarar" |

Filmado em 2005, em película 35mm,

também em um esquema completamente independente, sem apoio,incentivo ou

recursos, demorou dois anos e meio para ficar pronto. Lançado em festivais em

2008, Amarar dividiu opiniões. “Mesmo

que o curta seja um formato de experimentação para jovens cineastas no país, o experimentalismo

aqui vai muito além da montagem fragmentada responsável pela cristalização do slogan do filme: “um labirinto de

memórias”. Ele está muito mais expresso no jogo que cria com o espectador, no

sentido de atingir seu inconsciente; no lúdico da fotografia; na interpretação

de seus atores; no sutil e terrível subtexto de sua narrativa – a história de

um estupro (e não exatamente aquele mostrado no filme) –; no uso muito adequado

da trilha sonora (que utiliza três composições do estoniano Arvo Part) e dos

barulhos “estranhos”, criando uma atmosfera de sonho (pesadelo?) raramente

vista em curtas-metragens”, analisa o crítico Roberto Gonçalves Júnior.

“Em alguns momentos Amarar parece remeter ao sonho. Em seguida, nos coloca numa perspectiva

de visão de futuro, para depois se revelar como visão de passado, memória. E por

fim, trauma. A riqueza da história contada por meio de animação estática (que é a apresentação do filme), que revela

por zooms que nos aproximam e

distanciam do relato o tempo todo, pontuados por uma linda trilha sonora, é

perdida por uma conclusão de narrativa por meio de símbolos de uma vida perdida

e que se ausenta. Se em determinados momentos os signos do filme imprimem

alguma tentativa de riqueza, reforçados pelas presenças de Djin Sganzerla e da

histórica Helena Ignez, isso se perde na tentativa pesada do diretor em buscar

uma solução para aquela fuga idílica da personagem. O retorno à animação

estática no fim só revela tristemente que a proposta se perde quase que por

completo”, segundo Thiago Macêdo Correia.

|

| Djin Sganzerla em "Amarar" |

“Amarar é enigmático, curta poético, de alma feminina”,

diz Mariana Souto, jornalista cobrindo o Festival de Curtas de Belo Horizonte.

“Mas de tão misterioso, comunica mais beleza estética do que emocional, ainda

que sua trilha sonora denuncie que seu objetivo era também pegar pela emoção;

às vezes as notas graves são sentidas como desproporcionais, já que o que se vê

na tela inspira e enche os olhos, ainda que não comova – considerando-se que

esta era mesmo a intenção”.

Para alguns, esse não parece ter sido o

resultado – como bem comprovado pela rejeição ao filme pelo comitê do Festival

Internacional de Curtas de Clermont-Ferrand, na França, quando uma de suas organizadoras,

e responsável pela seleção dos filmes, sequer deu chance para que ele fosse

visto pelos outros membros, porque alegava ela que o filme lhe remetia a um

trauma de infância do qual ela preferia esquecer categoricamente. Após uma

série de emails trocados entre Mendes e um outro organizador, as tentativas se

mostraram infrutíferas, e o filme ficou de fora. “Ainda assim, ele teve uma

carreira considerável, foi exibido na Áustria, na Espanha, e alguns outros

festivais do Brasil”, diz André. “A maior dificuldade, é claro, foi a longa

duração – o que o impediu de entrar na grade de programação da maioria dos

festivais, os quais exigem quase sempre filmes até 15 minutos”, completa André.

Ainda nessa seara do fantástico e do

extraordinário, Emanuel Mendes escreveu o roteiro do curta O

|

| "O Homem Que..." |

Homem Que... (2011), dirigido por Yuri Tarone, produtor

multimídia que, à época, conduzia alguns programas para a MTV em São Paulo. “A

ideia inicial era na verdade fazer um documentário sobre a loucura, mas a coisa

tomou um outro rumo e resolvemos fazer um filme de ficção cujo tema era a

loucura”, diz Tarone. O Homem Que... foi

também importante para que Mendes fundasse sua própria produtora, a Sincronia

Filmes, um sonho há muito acalentado. E pela qual lançou seu mais recente

trabalho no formato – É Quase Verdade,

outra vez um média-metragem (com 27 minutos), e outra vez um filme aberto a

inúmeras possibilidades.

|

| "É Quase Verdade" |

“A grande diferença agora é que temos

diálogos”, brinca André Campos Mesquita, que voltou a se reunir com Mendes. “Mas

a estrutura de trabalho, o modus operandi

da narrativa, tudo continua a mesma coisa. Inicialmente, joguei a ideia para

ele de fazermos um documentário de verdade sobre mendigos de rua, mas ele me

devolveu dizendo que achava mais interessante fazer um documentário falso. E um

documentário falso não apenas seguindo a cartilha do mandamento desse gênero –

câmera na mão; filmagem em digital; em preto e branco etc –, mas um

documentário falso ironizando a eterna situação do cinema brasileiro em querer

mostrar e divulgar apenas a pobreza, a violência, o Nordeste e todos os clichês

do país em festivais mundo afora”, diz André. “E uma situação, inclusive, pela

qual ele sempre passou com os filmes anteriores – essa dificuldade de exibir o

diferente, o não-clichê. Pois bem, agora entregamos um filme onde a cara do

Brasil e do cinema brasileiro estão escancaradas, e, mais ainda, ironizadas. É

a pobreza não como cenário para histórias edificantes ou ditas, humanas, mas a

pobreza que emerge, te apontando o dedo na cara”.

Muito da incompreensão que cerca uma filmografia

em curso como a de Emanuel Mendes – e que, ironicamente, tem ecos com a de seu

amigo em longas, Guilherme de Almeida Prado, um dos atores de É Quase Verdade –, muito de sua

impopularidade em festivais e mostras, muitos de seus problemas e impasses, se

devem a essa imersão em uma época fragmentada e em uma proposta estética que

não se deixa apreender com facilidade. Pode-se gostar ou não dessa obra. O que

não se pode negar é a sua coerência interna.

Welcome to the special retrospective we have prepared on director

Emanuel Mendes, whose new short film, It´s

Almost True, is all ready for release. The film, a mockumentary shot in

black and white, and the third on the helmer´s filmography, has all the

elements and idiossyncrasies of this genre, but it also has the personal

trademark and style of its auteur, a

cinema which does not hide its vocation towards the fantastic and the

extraordinary inserted in the reality of everyday man. The text below contains

some testimonies as well as detailed analysis on the three shorts directed by

Mendes so far – Assis & Aletéia

(2002); Amarar (Wave) (2008) and, of

course, It´s Almost True (2014).

If the cinema is the combination of image plus sound, without the need

for dialogue, like Alfred Hitchcock (1899 – 1980) used to say, or the lie 24 frames per second, according

to the famous saying by Jean Luc Godard, or still according to what German

director F. W. Murnau said that the ideal

picture needs no titles, by its very nature the art of the screen should tell a

complete story pictorially, then the cinema of short films made by

Brazilian director Emanuel Mendes, born in countryside Minas Gerais and who

established himself in São Paulo in 1999, fits the bill accordingly. At least

the first two of his films, Assis &

Aletéia (2002), a love tale inspired by two of the director´s greatest

passions, Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel (1900 – 1983) and painter Salvador Dalí

(1904 – 1989), and Amarar (Wave) (2008),

also a love story with elements of the fantastic and the extraordinary, about a

young woman (played by Djin Sganzerla, daughter of Brazilian cinema´s enfant terible Rogério Sganzerla) lost

in daydreams, incapable of seeing the difference among past, present and

fantasies. None of the films contains dialogues, explanations or intertitles

that help the viewer dive in their labyrinth.

“What is going on there is not the action based on dialogues, but the

feelings and sensations of the characters”, says Mariana Tavares, from Rede

Minas TV, who interviewed the director for the 2008 edition of the Belo

Horizonte International Short Film Festival. “The films are not that black and

white, you have to set the puzzles in your head. It´s up to the viewer to form

his or her own story interpretation. This way, the films respect the public´s

intelligence”, continues Mariana. This obviously does not mean a secret to

success or an easier embrace by the audience. “People have forgotten how to

think – they´re too much tied to what they see on TV, on advertising, the

ready-made formulas, they want to leave the theater having understood

everything, knowing exactly who was the hero and who was the villan. If they

are challenged into thinking a little bit more, if they have to make an effort

to understand something, or even deal with ambiguity (which is something they

are mostly incapable of), and they can´t, they feel stupid, so the immediate

reaction is to reject what they´ve just seen”.

|

| Scene from "Assis & Aleteia" |

Assis & Aletéia, the first short by Mendes, has obviously not escaped this. Shot on

16mm, on locations in São Paulo and Pouso Alegre (a Minas Gerais town which

lended the filmmakers its small train station and locomotive as main sets), the

story is about a young man who casually meets a young girl (whose face we never

see) in a train wagon, becoming obsessed by her navel, the film provoked all

kinds of different effects at festivals – since its first screening at the

Gramado Latin Film Festival in 2002 until boos, shy applause and disconcerting

reactions from the public in general. “But it is a film where the strange and

the beauty are familiarly connected by desire”, says Francisco Costabile, a filmmaker

and a friend of Mendes´s. “The scenes of the two hands with the trees´s limbs

on the background, or even the fluttering white sheet seen from a distance are

examples of this. The feeling of weirdnness that the film arouses is very

strong, it even surpasses the actor´s performances, it is a completely

realistic situation of being inside a train wagon in a context we don´t want to

believe is true, but actually a dream”.

Written in 1995, by Mendes and his cousin, psychologist Christiano Lima,

Assis & Aletéia is inspired by

the short film Un Chien Andalou

(1928), directed by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, and considered the starting

point of Surrealism in the cinema. The story follows the starting point to that

of Buñuel and Dalí´s – “instead of an eye slashed by a razor, we had a navel

cut by a knife”, says Christiano. And also there´s a strange coincidence

regarding circular forms, the navel, the train wheels, the story´s narrative,

which starts and ends at the same spot. An obsession, btw, of Buñuel´s own

cinema, whose constancy had almost always been on situations and themes that

would repeat themselves. “We were so much in love with Buñuel and Dalí, by

their work method, that we decided to copy them”, continues Christiano. “We

agreed that, if we saw something interesting, on the street, anywhere, one

would immediately tell the other about it, and we would start our film from

that idea. And I happened to see: on the bus, on my way to College, I couldn´t

stop looking at a guy staring at a girl´s navel”.

|

| Actor Fernando Seth as Assis |

The result was a short that was really short in length, only 5

minutes, which today Mendes himself considers more like a learning lesson, a

film whose intention was better than the final result, but which, according to him, was like truly film school

experience. It was all produced and financed with his own resources, having had

FAAP (The Armando Álvares Penteado College), in São Paulo, as its main

supporter, the camera that was lended from friends, the film stock which was

out of date for at least six months, among other difficulties, but which were

all overcome by a young director who, until today, has not yet abandoned

exercising provocation and artistic independence.

“But this is all very costly”, says Christiano Lima. “The film was rejected

by festival audiences, many people came to ask us what the hell we wanted to

say with that, and there were people who said it didn´t look like a Brazilian

film – it was too European, too hermetic, too much influenced by foreign

cinema”. And this, according to director Mendes, in a format where

experimental things are all what it is about, where you can dare do things differently

more than on a feature film, which has rules and commercial obligations

inherent to their own sale and distribution. “We even had some people

complaining about the script, saying we didn´t even write a script, because

there were no dialogue in it. I think it´s sometimes scaring the intellectual

level of some of the people in this medium”.

|

| Djin Sganzerla in "Amarar" |

But the director continued faithful to himself, to his principles and

his aesthetic on his next move, Amarar

(international title Wave) (2008), considered, by Mendes

himself, his best film so far – a much more mature work, under all points of

view, the one that Mendes saw himself turned into a real film director,

according to his own words. Starting from the length itself: 23 minutes, when

the “normal” duration for this kind of film reaches 15 minutes in length. And a

film which also demands a tad more attention and perception on the part of the

viewer. And where he also learned how not commit the same mistakes from the

previous film, but instead be opened to the possibility of commiting new ones. The

idea came to Mendes after telling his friend and cowriter André Campos Mesquita

about an image that wouldn´t leave his head: the one of a young woman, lost on

a deserted island, with a giant cracked mirror by her side.

“Actually this image has a much more remote origin”, says André. “Once,

he told me, Emanuel went to Masp (The São

Paulo Art Museum) and was very much impressed by a picture (from naturalistic painter Johannees Thermin)

which showed a sad woman with a cracked vase by her side. That was the core to

our film”, continues André. After writing many versions of the script – “one by

each month, totalling six months, in a very fun and rich workshop process, but

also full of difficulties to fix the plot, to the point that we started

refering to the script as “that unpleasant subject””, says André – the duo made a

complex film, with many entrances and layers for interpretation. A love story –

involving the character played by Djin Sganzerla, Noemi – but also a tale of a

mature woman´s memories (played by Helena Ignez, mother of Djin´s, ex-wife of

Rogério Sganzerla), or simply the narrative of a little girl with an

extraordinary imagination, or even with one of a hell scaring childhood trauma

(the girl was played by newcomer Bruna da Mata).

|

| Bruna da Mata in "Amarar" |

Shot in 2005, on 35mm film stock, also under an independent strategy, it

took two and a half years to be completed. Opening to film festivals in 2008, Amarar divided opinions. “Even though

short films are a format for experimenting among young filmmakers, the

experimentation here goes far beyond the fragmented montage responsible for the

concrete slogan of the film: a labyrinth

of memories. It is much more expressed in the game play with the spectator;

on the ludic of its cinematography; on the actors´s performances; on the subtle

yet terrible subtext of its narrative – the story of a rape (and not exactly

the one shown in the film) –; on the very effective use of music (which

utilizes three pieces by Estonian composer Arvo Part) and the weird soundtrack;

all of which create an atmosphere of dream (nightmare?) rarely seen or felt in

short films”, analyses film critic Roberto Gonçalves Júnior.

“For some moments, Amarar

seems to take you into the world of dreams. Then it places you on a perspective

of the future, only to reveal itself as a vision of the past, of memories. And,

finally, of trauma. The richness of the story told as static animation (which is the beginning of the film),

which zooms in and out, pontuated by a haunting musical score, is lost out of a

conclusion in the narrative using symbols of an absent life. If, for some

instants, the film signs give you some attempt of richness, reinforced by the

presence of Djin Sganzerla and the historic Helena Ignez, this is lost in the

director´s attempt in finding a solution for that idyllic escape of the

character. The return to the static animation in the end only shows off that

the proposal sadly misses the point”, according to Thiago Macêdo Correia.

|

| Djin Sganzerla in "Amarar" |

“Amarar is enigmatic, a

poetic film, of a feminine soul”, says Mariana Souto, a journalist also

covering the Belo Horizonte International Short Film Festival. “But the fact is

it is so misterious, it communicates rather more aesthetic beauty than

emotional, even though its musical score denounces that the target was also to

emo; sometimes the low key notes are reverberated disproportionally, since what

we see on the screen fulfills your eyes, though it does not move you – considering

this was the intention”.

To some, this seems not to have been the result – as confirmed in the rejection

of the film by the official committee of the Clermont-Ferrand International

Short Film Festival, in France, when one of its organizers, and the one

responsible for the selection of the films, not only promptly rejected it but

also prevented the other members to see it, claiming that the film made her

remember a tragic happening of her youth that she prefered to forget forever.

After a series of brief email exchanges by Mendes and another member, the

attempts were useless, and the film was out. “Still, the film had a

considerable career, it was screened in Austria, in Spain, and some other film

festivals in Brazil”, says André. “The great hindrance, of course, was the long

running time – which prevented the film to be in most of the festivals, because

they usually demand 15 minute films”, completes André.

Still on the fantastic and the extraordinary turf, Emanuel Mendes writes

the script for the short The Man

|

| "The Man Who..." |

Who… (2011),

directed by Yuri Tarone, a multimedia producer who, at the time, was running

shows for MTV Brazil in São Paulo. “The initial idea was to actually make a

documentary about madness, but the whole thing took on a different direction

and we decided to make a fictional film whose subject was madness”, says

Tarone. The Man Who… was also

important for Mendes because it was through the film that he founded his

production company, Sincronia Filmes, a dream come true. And by which he is

also releasing his most recent effort in the format – It´s Almost True, again a middle

length film (27 minutes long), and again a film opened to countless

possibilities.

|

| "It´s Almost True" |

“The biggest difference now is that we have dialogues”, jokes André Campos

Mesquita, who reunited with Mendes again. “But the work structure, the modus operandi of the narrative,

everything is the same. Initially I threw to him the idea of making a real

documentary about beggars and homeless people, but he threw it back to me

saying he thought more interesting to make a mockumentary. And a mockumentary

not only following the traditional rules of this sort of genre – handheld

camera; shot on digital; in black and white etc –, but a mockumentary mocking

the eternal situation of Brazilian Cinema in wanting to show only the poverty,

violence, the Sertão and all the other clichès of the country in festivals

worldwide”, says André. “And a situation, BTW, that he experienced himself with

his previous films – this difficulty in showing what is different, the

non-clichè. Very well, now we have delivered a film where the face of Brazil

and the face of Brazilian Cinema are set wide open, and more than that, they

are mocked. It is poverty not as a scenery to tell “inspiring” or the so called

human stories, but the poverty which emerges, pointing the finger in your

face”.

Much of the

incomprehension which surrounds a filmography in the making like the one by

Emanuel Mendes – and which, ironically, echoes the one by his compadre and fellow director in feature

films, Guilherme de Almeida Prado, one of the actors in It´s Almost True –, much of its unpopularity in festivals and

exhibitions in general, many of its problems, are due to this immersion in a

fragmented time and into one aesthetic proposal that does not let itself absorb

so easily. You may like it or not. What you can not deny is its internal

coherence.